My favorite bridge, but this California girl may be biased

die Brücke. /di ˈbʀʏ:kə/ n. Language: German. Meaning: Bridge—a “soft,” “slender” and “peaceful” work of towering steel, according to those eccentric Deutsch.

Does the language you speak affect the way you think?

This question has been debated and beaten to a bloody pulp by every linguist worth his salt. Its origins lie in the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis, an idea of linguistic relativity that states that your inherent grammar shapes how you see the world.

Edward Sapir and his pupil, Benjamin Lee Whorf, sent shockwaves across the academic community when they suggested humans may not be as free-willed as previously thought—that in fact, something as decidedly unsexy as grammar could be dictating people’s thoughts and actions.

At first the idea took hold; to make a long story short, Whorf pointed out that Eskimo languages have so many variations for the word “snow,” so they must view icy precipitation differently than English speakers. People scratched their heads and thought, perhaps this guy has a point.

The idea is that each language includes or excludes certain things in its grammar. This leads speakers to be naturally more focused on certain things over others. Thus, observations are acutely tied to language.

But then most linguists came to their senses, realized ONE CASE STUDY does not warrant a hypothesis about all the world’s languages and speakers, and that, actually, Whorf’s procedure in measuring all this was faulty anyway. The theory was completely written off as silly at best, insulting and a-crime-to-the-field-of-linguistics at worst.

But in the bipolar field of language, the story doesn’t end there.

In recent years, linguistic relativity is making a comeback. There have been some fascinating experiments to show that maybe, just maybe, language can affect the way you see the world.

One that I find particularly convincing, as a student of both Spanish and German, was Stanford psychologist Lera Boroditsky’s focus on how grammatical gender could shape cognition.

Can Language Shape Thought: Linguistic Relativity in Gender

Background

Many languages encode for gender, by classifying their nouns into one of several categories. The gender encoding is usually arbitrary—there’s no reason a table is more manly or womanly than a houseplant—though most often, “woman,” “girl” etc. will be grammatically feminine, and “man,” “boy” etc. will be grammatically masculine. (There are some exceptions to this, though!)

The Process

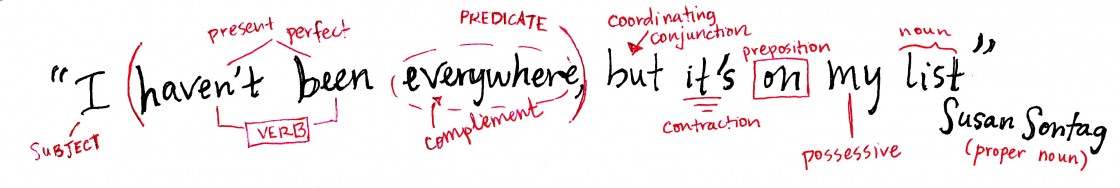

In order to check if languages with grammatical gender shape thought, Boroditsky rounded up a group of native German speakers and another group of native Spanish speakers. German has three gender agreements: masculine, feminine, and neuter–der, die, and das—and Spanish has two: masculine and feminine, el and la. These speakers were asked to describe the word key in English, which is grammatically masculine in German but feminine in Spanish. Then they were asked again, this time with bridge, which is feminine in German and masculine in Spanish.

You Try!*

How would you describe the words “key” and “bridge”?

I am a native English speaker, a fluent Spanish speaker, and a painfully slow learner of German, and the first word that pops into my head for “key” would be rusty. But then again, I’ve been using a house key that was first cut when Bush Sr. was president.

The Results

The native German speakers overwhelmingly described a key with such words as “jagged, rough, hard, heavy, metal, serrated, useful.”

Spanish speakers said a key was “golden, intricate, little, shiny, tiny, lovely.”

(Experiment aside, would you ever describe a key as lovely? Were these participants high?)

Next up was the word for bridge, which is feminine in German and masculine in Spanish. The results were consistent! German speakers described a bridge (in English) with adjectives like “beautiful, elegant, fragile, peaceful, pretty, slender,” all words that usually personify females.

Spanish speakers came up with “big, dangerous, long, strong, sturdy, towering,” much more stereotypically male attributes.

German gender can be quite arbitrary

- From “YOU TRY” above: If English is your mother tongue, then this attempt to try to involve you through a blog post was a hoax. English doesn’t encode for gender, so your answers are invalid, but thanks for playing!

Conclusions

Does one experiment across three languages mean that language shapes thought? Absolutely not. But think about the implications these findings could have if they do hold water.

The issue of gender in language has far-reaching effects that could be the next wave in not just linguistics, but feminism, psychology, communication. . . . English has already taken steps to replace terms like “fireman” and “policeman” with “fire fighter” and “police officer.” Is a little girl in Ecuador or Spain unconsciously deterred from realizing her dreams because there is no feminine form for the term “artist” or “dentist?”

If this study shows that the grammar of a language—in this case, gender—affects people’s perception of an object, imagine how it could affect the perception of people, culture, and relationships.

The verdict is still out on whether or not language can shape how you see the world.

But what I try to convey through A Thing For Wor(l)ds—whether approved by Sapir and Whorf or not—is that language can, and most certainly does, shape the way you travel and soak up new experiences and cultures.

In the coming weeks and months I will be highlighting language learners, sharing language learning tips for expats and travelers, and uncovering jaw-dropping facts about world languages that you would never conceive of as a native English speaker. All related to travel, of course, because why leave out half the fun? To keep up with it all, sign up for posts, and make sure to check out A Thing For Wor(l)ds on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and Pinterest.

Are you a believer in linguistic relativism, or does it seem like a hoax? And how has language shaped your travels? Let me know in the comments below!

Pingback: DMPK Studies()

Pingback: invitro pharamacology()

Pingback: www.cpns2016.com()

Pingback: My Thing For Words: Writing a Blog()

Pingback: Keys and Bridges: Can Language Shape Thought? |...()

Pingback: Language and the Future()

Pingback: language and THE FUTURE | A Thing For Wor(l)ds()